Report from the Clark Symposium: Photography as Model?

Last week, the Clark Center hosted a one-day symposium at the Arts Club of Chicago that aimed to “reflect on the models we currently have for discussing photographs as art.” Organized by Matt Witkovksy, the curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, “Photography as Model?” drew its inspiration from art critic Yves-Alain Bois’s 1990 book Painting as Model and asked six speakers—mostly art historians—to think about how the frameworks we use to examine photographs might shape the ways that scholars approach modern and contemporary art in general.

In this sense, the aims of the symposium were ambitious. To convincingly argue that photography studies might provide a model for art history as a discipline, or that individual photographs might model new approaches for seeing, is no small task. Especially when, as Victor Burgin has so aptly put it, “photography theory has no methodology peculiarly its own.” It often feels like photography theory has been cobbled together from several disciplines outside of art history, including cultural studies, film studies, feminist and queer studies, semiotics, and post-colonial studies. This flexibility is one of the things I’ve always liked about photography studies, but it can also make the discipline feel a bit nebulous: a feeling that’s compounded by the difficulties in even defining what a photograph is, especially with the advent of digital technologies (see David Campbell’s excellent post on just this problem over at his blog).

But I think these can be productive problems to have, and the papers that resulted from Witkovsky’s prompt to think about the productive disunity that characterizes photography as a field of inquiry bore out some of this potential. In his opening remarks, for instance, Witkovsky offered detailed readings of two very different kinds of photographs. The first was a spare, conceptual series of photographs of “‘hyper-banal’ subjects” by American artist Lewis Baltz; the second a group of four nearly-anonymous photographs taken clandestinely by members of the Sonderkommando unit at Auschwitz during the Holocaust. While the first is the product of an individual artist’s time-consuming process and is meant to be exhibited in a fine art context, the second is a group-authored image taken under life-threatening circumstances that was never guaranteed an audience of viewers (indeed, Claude Lanzmann has argued these photographs should not be shown). By offering these two examples, Witkovksy hoped to ask whether we could create a field of photography studies where these two kinds of images could be adequately accounted for within one broad and general history, a comparison he described as a “travesty” under the current theoretical models used in art history which would insist on separating these two series of photographs based on the identity of their producers and audiences.

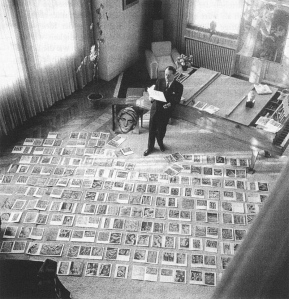

Georges Didi-Huberman, the first speaker, followed this insistence on the disunity that drives photography studies by analyzing André Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire (1947), a book project that sought to use photographs to create a new account of world art history based on formal similarities across widely disparate time periods and geographical locations (a video version of this talk appears on this documenta 13 website as well). Didi-Huberman’s focus was on the ways that Malraux tried to mimic the conventions of film editing in his formal choices for the book, and on how Malraux positioned the role of the art historian as that of an art editor who uses visual editing to construct a narrative about the history of forms. While Didi-Huberman’s main point was that photography has always been an “impure model,” constantly tied up in other media such as cinematography and literature, his paper was also useful in posing questions about how photography studies approaches an author who is not the operator of the camera, but rather the manipulator of already-made images.

On the other end of the spectrum of the artist-as-editor, Maria Gough offered a nuanced reading of the 4,000-6,000 photographs taken by Lotte Jacobi during a trip to the Soviet Union between 1932-33. Jacobi, a prominent portraitist who worked in the US from 1935 until her death in 1990, exhibited what Gough describes as “compulsive overshooting” during her stay in the Soviet Union, a condition encouraged by the invention of the lightweight and super-portable Leica camera in 1925. Of the thousands of negatives she created in this period, there is no indication that Jacobi ever exercised any selection or editing process, instead storing her negatives in a series of filing cabinets. As Gough observed, this approach to photography complicates our assumptions about when a photograph is “made,” refusing the reproducibility of the photographic print and insisting instead on the moment of creation as the moment in which the photographer selects a motif and decides to open her shutter.

The papers in the afternoon continued to offer alternative models for analyzing photographs outside of the traditions espoused by art history, including Iliana Cepero Amador’s reading of Luc Chessex’s photographs of 1960s Cuba modeled on Robert Frank’s The Americans; George Baker’s analysis of the role of the negative as a medium between visibility and invisibility in the work of Paul Sietsema; and Moyra Davey’s self-reflexive account of creating her 2011 video work Les Goddesses, which featured photographs of her sisters taken from very early in her career and signaled a return to figuration in her work, despite her misgivings about the ethical implications of publicly exhibiting these images.

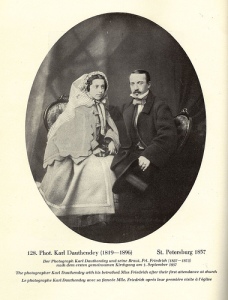

Karl Dauthendey, “The Photographer Karl Dauthendey with his betrothed Miss Friedrich after their first attendance at church, 1857”

The last paper of the day, by Kaja Silverman, returned to some of the meta-narrative questions about the pursuit of photography studies by examining a misreading from Walter Benjamin’s 1931 essay “A Little History of Photography.” As Silverman deftly pointed out, Benjamin misinterprets an 1857 portrait of German portrait photographer Karl Dauthendey as showing he and his first wife, who would later commit suicide, and claims that the viewer can see her despair in the photograph through her gaze, which is directed at an “unhealthy distance” outside the frame. The photograph is in fact a portrait of Dauthendey and his second wife, taken nearly a decade later, but as Silverman points out, the misidentification that Benjamin makes is a motivated one that points to the limits of the subject’s agency in photography. The “spark of contingency” that Benjamin said characterized the medium here makes itself felt through the network of gazes that are exchanged between subject and viewer, making a reading of the Dauthendey portrait as a portent of unhappiness entirely plausible. As Silverman convincingly argued, this mode of double-seeing—the viewer who looks at the photograph and the subject who looks back—is what makes photography a potentially revolutionary force in human relations and interactions, and one that is worthy of continued study.

Great Wedding photographer, I’m habitue visitor connected with on website, maintain up the excellent manoeuvre, and The idea’s likely to be a steady visitor for a long period.